Dennis "R.D." Steele, Owner/Operator, Steele Creative Services, Philadelphia, PA

by Jerry Vigil

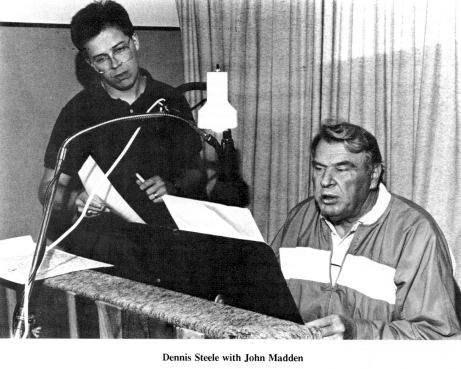

It's always a treat to check in with yesterday's Production Directors and find out where they are today and how they got there. This month we visit with Dennis "R.D." Steele, yet another graduate of WEBN's "school of production." Dennis spent some time at WEBN in Cincinnati before winding up at WYSP in Philadelphia which was his last stop in radio before taking the big leap into self employment. Dennis now produces "John Madden's Sports Calendar," a syndicated sports program heard daily on over 150 stations; and his voice-over business is off the ground and doing well. Some of his voice-over clients include Kraft Foods, TV Guide, Pizza Hut, McDonalds, AT&T, Campbell Soup, and Cigna Insurance. Dennis shares some insights into syndication as well as some tips on making it in the voice-over business. Join us as we get a look at a former Production Director with a colorful resume and a bright future.

R.A.P.: Tell us about your background in radio.

Dennis: My interest in radio started at the University of Cincinnati. I wanted to be a film major, but I got into radio via Tom Sandman whom you interviewed recently. Tom and I went to the same high school together in Cincinnati, and he was the one who turned me on to UC when I was looking at colleges. When I got there he said, "You really ought to check out WFIB, the campus radio station." So I did. November of 1975 was the first time I was ever on the air anywhere for any reason. I was on college radio all through college. Then in '76 I got an internship at WSAI-AM, which was, at that time, a powerhouse top forty AM. I did midnight to six on Sunday nights for the entire semester. That was pretty cool. By the summer of '77, Sandman was the Production Director at WEBN in Cincinnati, sort of the nesting place of a lot of good production people. Tom called me up and said, "Hey, what are you doing this summer?" I was spinning records at clubs, working at a fast food place, working two and three jobs to try to pay off college. He said, "How would you like to work as my assistant in production?" My experience in production was campus radio. I had done very little. I got straight Cs in my audio production courses, and I was a total spaz at the technical side of production. But I said, "Sure! Of course!" Who wouldn't? It was the radio station I listened to, and I listened to it practically since it signed on in 1967 as a progressive radio station. So I worked there three days a week in production, and then I started doing overnight weekend air shifts.

When the summer was over I was supposed to stop and go back to school. But bad things kept happening to people on our air staff, like our Program Director blew out his knee at a company picnic and couldn't get his cast under the console, so they needed jocks to fill his slot for six weeks. I got to fill in doing production while other people were doing air shifts. Then something would happen to somebody else, or somebody would go on vacation. I hung around at the station for the next fourteen months and basically got a regular weekend air shift. I became sort of a fixture around there.

Bo Wood, the General Manager, helped me scam a co-op out of it. I ended up getting twelve credit hours for working there, and I don't know if I would have graduated if I hadn't received that. Anyway, it was just an incredible place to work, and I basically learned everything about radio and about production and theater of the mind while I was there. It was a great experience from top to bottom. It was terrific for a young guy -- twenty, twenty-one years old -- to go in there and meet rock stars back stage at concerts and all the stuff that was a bonus on top of the incredible learning experience.

But all good things come to an end, and when I got out of school, there really was not a full-time job for me there. I sent tapes everywhere. Then a friend told me there was a start-up operation in Des Moines, Iowa. KGGO radio in Des Moines was going from Paul Drew Top Forty to an Abrams Super Stars formatted FM AOR station. I packed up my Pinto wagon and all my earthly possessions, and in August of 1978 I moved to Des Moines, Iowa as Production Director for this new station. That was a real trip because Des Moines was a very strange market in terms of rock radio. They had an AM AOR station that was very well thought of, and they had a cable FM progressive rock station. We were the first FM AOR station in the market. Des Moines is the biggest city in Iowa. It's a town of about 300,000 metro, and it's the state capital. There's Iowa State University, and there's Drake University. There are all these college students and all this activity, a lot of concerts. They have a big State Fair, too. It's a really great place. I was Production Director, I was Music Director for a little while, and I did nights for a while. I sort of completed my Masters degree here at KGGO. You know, my undergrad work was at 'EBN, and my post-grad was at KGGO.

KGGO had an AM station, too. The AM was KSO, Great Country, and they were the big country station in the state. Here you had all these jocks who literally wore cowboy hats and bolero ties. I'm serious, and they would have chili cookouts in the lobby on Saturday afternoons. Then down the hall there were these long-haired, bearded guys playing album sides. There was a real culture clash there. This was also the only radio station I ever worked at that had a swimming pool, and it was there for our use -- the whole two weeks that it was warm enough to go swimming. It was a wild place, and the management really didn't know that much about rock and roll and what we were trying to do. So we got away with a lot of things. It was still really getting off the ground when I left.

R.A.P.: Why did you leave?

Dennis: I guess I was doing a pretty good job because they fired the AM Production Director and came back and said, "We fired the AM Production Director, so you've got the job of doing AM and FM production." And I said, "Well, will there be a raise attached to this?" And they said, "Yeah, we figured we'd give you another hundred bucks." I said, "A week?" "No, a month." I basically said, "If you do this, I'm going to quit," and as soon as I found a job, I left.

In 1979, WWCK in Flint was looking for a Production Director, and I got the job. This was a number one station in a market that was just unbelievable. Flint was a very crazy town in those days because fifty percent of the people there worked in auto manufacturing for General Motors. So, there was no such thing as morning rush hour. There was no such thing, really, as day-parting. It was basically rock all day, rock all night, as hard as you can because there were people always getting off third shift. They would be up at seven-thirty in the morning ready to party, man! We had a pretty good time there.

After I got married we decided we didn't want to live in Flint forever, and at the same time we were thinking about that, I got a call from WYSP in Philadelphia. I had done a song parody in Flint called Flint-oids, a parody of Miss You by the Rolling Stones. Basically, it was a homage to our listeners. We had started calling them Flint-oids on the air. They were also known as "gearheads" -- guys who worked at the plant, partied hard, and loved loud rock and roll like Ted Nugent and Bob Seeger. So instead of sort of making fun, we turned it into a positive and said, "being a Flint-oid is a cool thing." They call it building your self esteem today. So we did this parody called Flint-oids. WYSP heard it and called and said, "Our Production Director, Jay Gilbert, is leaving. Would you like to take his job?" I moved to Philadelphia and started working at 'YSP.

This is where I met Gary Bridges. I work with Gary on the Madden shows. I also met Denny Somach who went on to do a lot of great things in radio and television. As Production Director at WYSP, I no longer had an air shift, and I didn't cut a lot of commercials any more. I started to do promos and image enhancement and contribute comedy and voices and silliness to the morning show. Then I started working with Denny on Denny's syndicated projects. Denny was working closely with The Source, which was NBC's young adult network. A lot of stuff that was going on with The Source in 1979 and 1980 was coming out of 'YSP. I got involved in that. I started out doing montages for their shows and then started writing shows and then producing shows.

Then in 1981, Denny was leaving the company to start his own radio production company, and he asked me if I wanted to co-produce a radio show with him called Rolling Stone Magazine's Continuous History of Rock and Roll. At that time, ratings were starting to slip, and the company was in the process of being sold. If you've ever gone through that, you know no capital gets spent. No improvements are made, and things are just allowed to let slide. I figured it was a perfect time to jump into syndication. So, at the tender age of twenty-five, I retired from being a radio Production Director and started producing this radio show with Denny for Rolling Stone Magazine Productions.

Denny and I co-produced the show, and our host was Gary Bridges who we had worked with at 'YSP. We did that for two years, and the contract ran out on that. That's when I found myself for the first time kind of sucking air looking for something to do. Then I got the idea to go out on my own and try to be a free-lancer with voice-over, writing, and production. It didn't take off right away. Although I did end up doing a lot of free-lance work for 'YSP. This was in 1983, and by this time they had hired Bob Stroud, who is a terrific production guy -- one of the best I know.

I eventually got hired by the morning show at 'YSP to provide comedy material. I would work out of my house writing material, and then I'd take it to the station. Whenever I could get into the production room, I'd put it together and give it to their morning show. Well, that sort of snowballed to the point where they were using me more and more and getting more and more of my invoices. Finally they said, "We're paying you too much as an outsider. How would you like to come in, and we'll make you sort of a producer. You can help out Bob Stroud in the production room, but it's really kind of an excuse to have you come in from six to ten in the morning and just sort of hang out and write and produce comedy bits and do funny voices and whatever the morning guys want you to do?"

So in 1984 I was doing mornings at 'YSP. Then Bob Stroud left to go back to Chicago, and they made me Production Director again. Then I hired an assistant, Ron Lipkin who was out of KLSX in Los Angeles.

I did this from 1984 until Labor Day of 1985. Meanwhile, I'm generating all this comedy material, and I got a call from the American Comedy Network. They asked me if I wanted to be a contributor to their network. Those two years, '84 and '85 at 'YSP, were some of the best times I had because here I was working on the morning show sort of as a sidekick, doing funny voices and whatever we came up with. Then, if it was good, 'YSP allowed me to lease it to the American Comedy Network.

Then in 1985 we had another change in management, a new Program Director came in and cleaned house on Labor Day. Then came Denny Somach again with a job offer, and I became the Director of Programming for Denny Somach Productions from 1985 to 1987. We embarked on a pretty big expansion and produced a number of shows. By this time his clients were DIR, Ticket to Ride, the Beetles show. We did projects for NBC, ABC, Westwood One, The Psychedelic Psnack.... We did quite a few shows, and it was really just a great experience. I got to work with Billy Crystal, Bob Costas, Mary Wilson of the Supremes, Dave Herman, Scott Muni, and Joe Piscopo. It was a great time for syndicated radio, and I got to do a lot of writing and producing. I got to oversee other writers and producers and was able to see how the radio syndication business works.

I left there on pretty good terms with Denny, although I found over the years that he and I work better when I'm free-lancing for him than when I'm working for him. But we still work together occasionally. I just did a project with him last September for Premiere Radio Network. Denny's off doing some incredible things with a company called Musicom International, and he's doing quite well.

So I left him in 1987 and started free-lancing on a full-time basis. I started submitting voice-over tapes to advertising agencies in Philadelphia. I had been doing it here and there since 1982, but I really started getting work that spun off from my morning show gigs doing voices, song parodies and stuff like that. Then one job begets two begets four, and it just sort of builds.

Then Gary Bridges called me in 1988. Gary was writing and producing a show with John Madden called The John Madden Sports Quiz for Olympia Networks. He asked me if I would be interested in writing funny sports stories for the John Madden Sports Quiz show. I said, "Sure, I'd love to." Then in the fall of 1988, Olympia decided to spin off another show from that one called the John Madden Sports Calendar, which was aimed at a different audience, and they asked me if I wanted to produce that show. I developed the show from the demo on up, and I've been producing it ever since.

R.A.P.: How's the voice-over business treating you?

Dennis: That's going very well. Currently, I'm real busy. But, if you've ever done voice work on a free-lance basis, you know that it's feast or famine. Everybody seems to be hiring at the same time or no one is hiring. It goes in cycles.

R.A.P.: So, when you're not doing voice work, you're working on the Madden program?

Dennis: Yeah, I work on the Madden show. The Madden show is now distributed by a new company, Major Sports, out of Chicago. Chris Devine is the owner of Major Networks, and Jeff Schwartz is the head of Major Sports. These guys are Chicago radio guys from way back, and now they have this new company. They're distributing the Madden show and two Bob Costas shows plus a show with Pat O'Brien. They're currently developing programming for the future, and Gary and I are involved in helping them develop that. It's very exciting.

R.A.P.: Is the area of syndication large enough for production people to pursue as a sideline much like you did, or is it confined to a small group of people these days?

Dennis: I would say that syndication has shrunk over the years. All you have to do is look at what's happened to Westwood One and Unistar and NBC and Mutual. They're all one company now. They used to be separate. There's been a lot of combining, and it's certainly shrunk in terms of the number of people who have been involved. It's been downsized just like everything else -- fewer people doing more. I wouldn't say it would be a great time for production people to go out and say, "Hey, I'm a hired gun. Hire me to produce a syndicated show." I think the production people who would get work in syndication would be people who already have a great idea and already have a show that's pretty well fleshed out, and then try to pitch it to a network or a syndicator. That's probably the best way to get a show on the air if you're a producer.

R.A.P.: Before anybody tries to get some free-lance voice work they need a demo. What advice do you have to putting together voice-over demos?

Dennis: I think the most important thing you do before you put a tape together is find out who you are in the market. What I mean by that is find out where you fit in. If you're a top personality in your market, chances are you're not going to be hired by an advertising agency to do radio or TV voice-overs because they're looking for voices of people who sound like anybody. They don't want a personality. They want types. In my case, I'm sort of the anti-announcer. I don't really have a ballsy announcer voice, and I get hired a lot as the regular guy, the normal guy, the typical dad, the typical husband -- "Honey, I'm home." So the best thing you can be is anonymous.

Secondly, you want to fit a niche. If you do have a great announcer voice, there's plenty of work out there for people like that. If that's who you are, then that's your niche, and that's what you ought to go after. If you do incredible characters and incredible dialects, better than anybody you know, that's where you ought to head. Then you make a tape. My first tape had song parodies on it, and it had me doing comedy dialects and my straight voice. I really didn't get any work from it. A friend in the advertising business told me to narrow it down, find a niche, and then fill that niche. So that's what I did. After listening around, I decided I was going to do a "honey, I'm home" regular guy tape. Finding a niche was the best advice I ever got.

Then I made my second tape. Make your tape very narrowly focused, especially when you're starting out. Focus on what you do best, and then hammer that for two minutes. And you want colors. If you're doing a straight read, you might want a more up tempo read, then a slower read, then a quiet read. But you want maybe two minutes of quick cuts of basically the same type of approach.

Once you start getting work, then you're in the door and people know you. Once they know you, then you can start surprising them. When I update my tape now, I don't really look for types of reads, I look for actual spots I've done that are either high profile spots or spots that a lot of people have reacted to. These are the ones I put first on the reel, so the response is like, "Oh, he's the guy who did the Pennsylvania Lottery. "Oh, he's the guy who did the Regional Transportation Authority spots." "Oh, he's the guy that did that funny thing on TV" -- things that are high profile that people recognize and talk about. And you say, "Yeah, that's my voice." That's what you put first.

Now I send out a two-sided tape. One side is straight reads, and the other side is characters and dialects. If I were producing me, I would know other people in the market who probably do character voices better than I do. But the people who already know me, well, now they've got something else to listen to, and they'll say, "Oh gee, I never thought of him as a guy who could do this." Then, once you have a reel like that for commercials, you need a reel for narrations, and industrial television and video, and sales presentations. A lot of people are putting their advertising and marketing dollars back into point of purchase and selling, helping their sales departments sell better, and they're putting together videos for all kinds of things, non-broadcast things that never go on television or radio. That's a booming business, and that's where a lot of voice-over people are needed as well. And you need to come up with another tape just for that segment. I've got a demo for about every sort of thing.

R.A.P.: How often should a person update these various demo tapes?

Dennis: I always use six months to a year as a good bench mark.

R.A.P.: You've made a lot of contacts along the way. Has this been a big part of your success in the free-lance arena?

Dennis: I am really the product of networking. I've always worked and collaborated with people I've worked with before. And with the help of friends, getting their advice and making contacts, I've been able to get where I am.

R.A.P.: Do you have a studio at home?

Dennis: Well, believe it or not, I don't have a studio per se. I basically have an editing station. I resisted the temptation to build a studio because I really like working with an engineer. Have you ever tried to fix a car these days? It's impossible. Cars are so complicated now, and there are people out there who are specialists just in tune-ups and emissions testing. I could run my own board and do the knobs and dials, but I prefer to work with an engineer. I do that with the Madden show, and I hope to do that with future shows, if I can.

But what I have at home is basically just an editing station and a writing station. I have two Panasonic SV3700 DAT machines, a CD player, a double bay cassette deck, an Adcom straight line converter which I plug everything into, and I have an old Teac reel-to-reel. I even use the turntable about once a month.

R.A.P.: What all is involved in putting the Madden show together?

Dennis: When we put the Madden show together, I decide on what we're going to do that month and I buy tape, sound bites from a whole list of stringers around the country, guys who interview sports people for a living and then sell us hunks of tape. Then we take that and combine that with Madden's commentary which I write, and that becomes the John Madden Sports Calendar. When I get all this tape from all over the place, I write my scripts, time the segments, and then decide which pieces I'm going to use for that one month. I load that onto one reel of tape. Then, if I need to edit it, I edit on the reel. However, there will come a time very soon when everything will be done digitally. That vocal tape is then sent to Chicago where they put the shows together. A guy by the name of Jeff Collins who is our new engineer does the final mix of the show. He gets Madden's tape, our scripts, and my vocal reel; then he mixes the show together.

R.A.P.: So you're writing scripts for John Madden around these sound bites, and John comes in and reads the scripts, not really knowing what he's going to say about one thing or another until he sees the scripts. Writing for someone like John must be a challenge.

Dennis: I think the thing that has helped us continue with the show is that Gary and I sort of know Madden-speak. We know how he talks, and we stay in contact with John. Gary produces the Quiz and I produce the Calendar. and we pretty much know how he feels about things. If we have a question, we call his office and say, "Hey, John, how would you react to this?" Or at a session we'll say, "What do you think of this guy?" or, "How do you feel about this?" Sometimes he'll stop us in the middle of a script and say, "I wouldn't say it that way. This is the way I would say it."

The guy has forgotten more about football than I'll ever know, so you don't want to mess around with getting the facts wrong. That's probably the hardest part of writing the show, staying on top of what's happening in sports. And then you have to make it silly, wacky, and amusing. We try to look for the weirdest sports stories we can find. Some days are weirder than others, but that's been sort of the goal of that show, to be date specific and create a fun show that sort of features John's personality and also goes beyond the newspaper stories and gets to the watermelon seed spitting championships and the outhouse racing and the Midnight Sun Golf Classic. We cover as much silly stuff as we can.

R.A.P.: You teach a radio class at the Art Institute of Philadelphia. What are some of the things you try to teach the students?

Dennis: They have a division there called Music and the Video Business and they teach audio production, video production, and music publishing. I teach Radio Programming and Production -- that's what it's called. I bring them in, and the first thing I tell them is that they already know a lot about audio production because, by the time I get them, they're in their second last semester -- it's a two-year course -- and they're learning ProTools, they're learning multi-track audio, they're learning video and syncing things up to video. They're already pretty sophisticated by the time they get to me.

What I do is I try to teach them things they can't learn in books, like how radio works. I try to pound into them that radio is about revenue and ratings, and that's basically what makes radio work. And you can't have one without the other, and that's why radio sounds the way it does.

A lot of kids tend to come into my classes with a chip on their shoulders about radio -- you know, the old REM song, Radio Sucks. A lot of people feel that way, especially kids like them. A lot of these guys are musicians, wear a lot of black, have pierced noses, and they come in with an attitude that radio is sort of alien territory. They ask, "Why don't they do this, and why don't they do that?" So I tell them why, and we talk about it. And by the end, I think they have a pretty good understanding of how radio works.

From a production standpoint, I stress writing. Writing, writing, writing. If you can't write a declarative sentence, you're not going to be able to communicate. I stress that radio is communication, and it's communication via the human voice. And you have to create word pictures because it's theater of the mind. Really, I'm teaching all the stuff I learned from working with the 'EBN people, how to make radio interesting just using words and word pictures. They have projects they have to turn in, and we try to have a lot of fun. I try not to be boring.

Our radio production facility there is not very sophisticated. It's simple stuff. I say to them, "Everything you want to do in radio, you can do in this room, but you have to use your imagination. You can't rely on all the things down the hall in the multi-track studios." It's basically a 2-track operation. It's got one Otari, a compressor, one equalizer, a CD player, and a couple of cart machines. It's very basic, but I try to stress that they know how to do basic production already, so let's make some interesting, creative radio. I try to get them to think creatively. I also teach them the fundamentals of editing sound bites into a project, making music work with a piece of audio, and we do a little documentary and a telescoped air check. We try to go to at least one radio station for a tour every quarter. I bring in friends of mine -- Account Executives, talk show hosts, and guys I know from town -- and we get into arguments. It's kind of fun. Most guys who come in aren't going into radio, but I think when they go out they like radio more than when they came in.

R.A.P.: What do you try to teach them about theatre of the mind production?

Dennis: I try to give them nuts and bolts. You can't really teach creativity. I mean, you've either got it or you don't. You either think creatively or you don't. I don't think you can teach somebody to be funny or be creative. But if you're creative, then you can learn how to channel it, how to get down to the nuts and bolts, what to do and what not to do.

From a writing standpoint we try to teach the basics: Who is your audience? That's the first thing. Who are you talking to? I try to teach them that radio is a one on one experience. When you're listening to the radio, you're not usually sitting by the radio listening to it. You're usually by yourself doing something else. You're in the car driving. You're at the beach sunning yourself. You're doing the lawn. So think about what people are doing when they're listening and then communicate one on one. And the words you're using should have a "you" kind of involvement and a one on one involvement. So you avoid words like, "Hey, guys" or, "Hey, everybody" because you're not talking to guys or everybody; you're usually talking to one person.

We talk about demographics. We talk about lifestyles and how radio is a lifestyle medium. I tell them to try to avoid slice of life commercials that are very hard to pull off unless you have (A) great actors reading your copy, or, (B) you're doing a parody on it because most slice of life commercials are so awful. The location...nobody ever says, "what's the location?" "What's that number again?" I also tell them never to write phone numbers in a radio spot unless they absolutely, positively have to.

I only have them once a week, so I don't have a whole lot of time to get too deep into any one thing. We've got eleven weeks; basically we have forty-four hours to teach them the history of radio, all about announcing, all about writing, all about equipment, all about ratings and research and how stations make money. So it's really an overview.

R.A.P.: Your teaching a lot of good radio basics to some people that may get into the business to find things quite different than we found them ten years ago. You've kept up with the LMA and duopoly madness that's been going on. What thoughts do you have on this latest trend in radio?

Dennis: It's still shaking out, and we don't know really what's going to happen. I'm sort of disturbed by it, but I don't know why. I understand from a business point of view why it's happening. Part of it is deregulation. Why are we doing this? It's because we can.

R.A.P.: How do you think it will affect the Production Director of the future?

Dennis: I think the best production people in the next five or ten years are going to be production people who are extremely organized, and I would suggest that rather than take lessons in creativity, you take lessons in time management. I was in a situation at one point in my career where I was responsible for five shows. I wasn't producing five shows, but I had to at least know what was going on in all of the shows so that if I got a call because something was going wrong, I knew what was happening. A Production Director with three or four stations will have to be extremely organized and have to be able to say, "Well, what's the most important thing I have to do right now? What's the most important thing I have to do today? What can I delegate?"

And I think we constantly have to be on the lookout for people who can help us. One nice thing about teaching is that I meet young broadcasting people. Occasionally, one or two out of a class are really interested in radio and audio. It's good to keep tabs on who is out there because you never know when a lot of work is going to come in, and you may need to farm something out.

Doing more and more with less and less is going to get you only so far. If I were a Production Director today, I would be very organized. And if I wasn't organized, I would figure out how to get organized and make sure I could do the work so that the station's sound won't suffer. The whole switch to digital from analog is going to create lots of ways to save time. It's just incredible the amount of time you can save with the digital editing systems. I worked on a digital workstation for the first time last summer. I used to work on montages that would take twelve hours to do. We did one in three. That kind of stuff will save a producer time, but in the end, there's only so much one person can do. So that one person has to become more efficient if that person is to have a life outside the radio station.

R.A.P.: What thoughts would you pass on to managers and Program Directors regarding their Production Directors?

Dennis: Your production people are a rare breed. They combine technical expertise with creative expertise. And producing commercials is a very specialized thing. I've watched big advertising agencies produce radio commercials, and very seldom, if ever, do you find technical people who are also adept at being creative, not to mention being able to voice the commercial, too. So, a production person is a real rare breed.

If you're a Program Director and you find a good one, take care of them. Be good to them because if you can get somebody who can write, who can enhance the image of your station and turn the biggest negative you have, which is commercials, into a positive thing that will keep your listeners listening longer, you've got somebody who has a rare talent, and you should nurture them, keep them happy, pay them what they are worth. They're on your radio station sometimes eight to ten minutes out of the hour which is more than your jocks are on any more. It's a big investment that you make.

A production job is basically a job that doesn't have a career path. Look at who gets promoted at radio stations. The General Manager generally comes from the revenue side. The Program Director generally comes from the ratings side. And the production person is generally kind of in the middle of programming and sales. He has to sort of serve two masters but, of course, usually reports to programming. Where does a Production Director go when he or she wants to advance in the company? There really isn't a career path for a production person. They reach a certain point, and they can only make a certain amount of money. The budget only allows so much for a production person, and after that, where do they go? They have to go sideways. They can't go up. So it behooves management to look at that person and treat that person with a lot of care and a lot of respect.

I have a lot of respect for Production Directors, not just because I was one a long time ago, but because it's very difficult work, and the more combining of stations we do and the more duopoly that comes along, these guys are just going to be doing more and more and more. And they don't have that promise of a place to move up, not unless they want to go into programming or management. You can do that, but then you basically have to get off the track you are on. So I just say, if you've got a good one, keep him happy.

R.A.P.: What's down the road for you?

Dennis: Right now I'm expanding. I want to do more work for Major, and I'm a free-lancer, so I am available to anybody who will hire me. But I really like Major's focus, and I really like where they are going. I'm really excited about developing new programs with them during the next year. I may be expanding my room here away from the editing station and more towards production, but I don't have any walls built yet.

A lot of my goals are personal goals. I have three kids, and they need a lot of care and attention. I really enjoy the flexibility that being a free-lancer allows me. If I want to take off early one day and go see my kid play soccer, I can do that. And because I work out of my house, I see my kids a little more often, I think, than the average dad does who is working twelve hour days. When I'm working and go down to get a cup of coffee on Saturday morning, they are there and I get to see them.