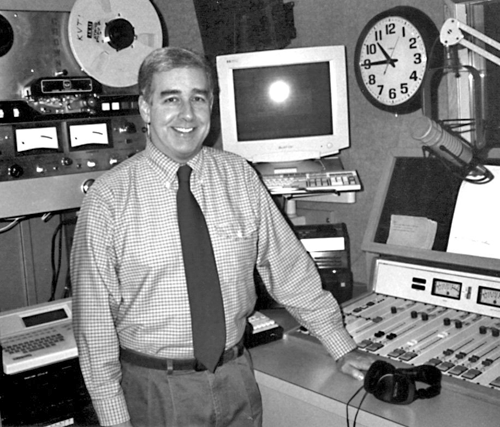

John Mangan, General Manager/Instructor, KVTI-FM, Clover Park Technical College, Tacoma, Washington

by Jerry Vigil

Where are tomorrow’s radio pros coming from? Some of them are coming from Clover Park Technical College in Tacoma, Washington. The college offers an extensive course in radio, headed by long time RAP member John Mangan, instructor, full-time faculty member, and General Manager of the campus station, KVTI at 90.9 FM, a.k.a. I91. This month’s RAP Interview peeks at the radio course offered at Clover Park, which includes a healthy dose of production, and we hear some production work from the students on this month’s RAP Cassette.

JV: Tell us about your background in radio.

John: I’m one of those people who decided radio was pretty interesting when I was about ten or eleven years old, and I had the advantage back in my childhood years in the early sixties of having a large AM/FM/TV facility about two blocks from my house. When I was in the sixth grade, I would go hang out there after school, which would be about impossible to do today with security guards and everything else. But that was a different time, and you could just walk in. They were more than happy to have a couple of us hanging around after school.

Then I got involved in public television as an intern doing studio work and audio when I was in high school. In college, I got involved in college radio and worked part-time in commercial radio, and in my senior year I did audio for a public television production center that was just getting off the ground in Ithaca, New York.

After some time in the Navy, I went to work for GE’s broadcasting division in Schenectady as a management trainee. I worked in business and finance and promotion in Schenectady and then in Denver in marketing and radio programming. I went from there to Seattle/Tacoma as an on-air PD at a country station, and then I went to an easy listening station.

JV: When did the idea of teaching come about?

John: The idea had been in the back of my mind for a long time, and I had written a term paper in college about a model for learning broadcasting in a competitive technical environment—a real working station, not a campus radio station—with some kind of professional management and engineering support in a technically competitive facility for students as a way to learn broadcasting in a real setting. Then, about eighteen years ago, I married a woman who taught at a 2-year college in town, and we were starting a family. She handed me the classified section of the paper one day and said essentially, “Put your money where your mouth is because this school is advertising for a radio broadcast instructor and station manager.” At that time, they had a 39 kilowatt FM that wasn’t really operating as a station but more as a lab setting. But the idea really appealed to me, and I’ve been here ever since.

Over the years, there’s been a lot of work on curriculum development. We’ve gone from being a voc center to a 2-year college with an associate degree program. So the curriculum has been through a lot of rewriting and redeveloping over those years, and the station has changed from being a little neighborhood six-hour a day station to a fifty-one kilowatt, twenty-four a day station that’s consistently one of the top four or five out of about fourteen or fifteen public stations in the Puget Sound area.

JV: Describe this market.

John: Well, Seattle/Tacoma is the metro, but it’s a big six-county metro that’s almost a hundred miles across in hilly terrain. So, it’s pretty difficult for a lot of stations to cover the whole thing. There are about seventy signals in the market in total. It’s the 14th metro in the country, a very competitive market with some great broadcasting going on —terrific people and terrific stations in every kind of format you can imagine. And of course, it’s very Seattle centered as most hyphenated metros are. The big city has most of the mailing addresses. We’re located in Tacoma, the second city in the market, actually just south of Tacoma. It’s been kind of a change since deregulation because there are a lot of Tacoma-licensed stations that used to physically be here, and most of them have moved to Seattle or the Seattle area, leaving the schools and a couple of smaller commercial stations operating in Tacoma and Pierce County. It’s a little lonelier down here than it used to be ten years ago.

JV: You mentioned having 14 or 15 public stations in the market. That’s quite a few for one market!

John: Yes. In fact, in the total market there are two NPR stations, and then a whole handful of community access stations of one kind or another that are owned by either private foundations or universities or school districts. There are high school stations and there are stations in the two-year college system, and they exist in both the public and private schools. The density of stations licensed to educational institutions here is phenomenal, and they range from quite large operations to very small. We still have a ten-watt FM at one of the high schools in the market that’s on the air every day. And at the other end of the student spectrum, there’s us with our fifty-one kilowatts and Seattle Schools’ KNHC at thirty kilowatts and some other sizeable operations.

The NPR stations have the largest audiences, and those are big stations. KOW at the University of Washington is a talk and NPR station and is a terrific facility. KPLU, which does have its main studio here in the Tacoma area at Pacific Lutheran University, is a jazz and news station and a regular national award winner, a terrific mainstream public station. The two high power FMs in the public area that are really a little out of the ordinary for public radio are our station and Seattle Schools'. Both of us are doing contemporary formats, but they’re not the same. Our format is kind of a mainstream, broad-based top forty format, so we’re really doing public radio for young adults and teens. If you can think of a cross between non-commercial radio and MTV, that’s kind of where we are.

JV: With so many college and high school stations, it sounds like the market is an extraordinary one for people to learn radio.

John: It’s a terrific area for that. In fact, I think if you grew up here you might think it was normal for high schools and colleges to have sizeable radio stations because so many of them do. And having grown up and worked in other parts of the country, I know that’s not true, but it certainly looks that way around here. And it goes way back. This station went on the air originally at a high school in 1955.

JV: Describe the radio course at Clover Park Technical College.

John: It’s a fifteen-month, year round schedule, so that’s equivalent to two academic years but done on a continuous basis. It’s a two-year degree program. We cover every aspect of radio station operations except for the technical equipment repair. We don’t get into the real nuts and bolts of the engineering end. We teach people enough engineering language and enough equipment knowledge to be able to communicate with engineers, but not be one. We put equal emphasis on business marketing, promotion, audio production, and on-air production and journalism. And then around that we have some broadcast history, ways to build a career and look for a job, how stations are organized, programming strategies and formats and that kind of stuff.

JV: How much of the course it is about production?

John: Well, it’s probably around a quarter to a third of it total, although there’s so much overlap from one area to the next. I’ve been a little bit devious in how I’ve designed the course modules. For example, one of the early studio experiences that students have is putting newscasts together, and they start out in a lab setting doing that on tape. So, their earliest hands-on production recording is actually doing the lab assignments for their journalism work. But to do that, they have to be conscious of mike placement and level settings and recording and playback and dubbing and all that stuff. So they’re getting some real beginning production basics that are contained within assignments in another course area. And a lot of these things that we do are layered together like that, so that you’re really covering multiple things at one time and may not even be aware of it.

JV: When you get directly into the production aspect of the course, what are some of the primary things you teach?

John: Copyrighting and the basic technical stuff. We start with analog production. This is a really interesting time to be doing broadcast education because of all of the changes in technology, and there are days when I think this would be easier to do as a business rather than a college because we could just be using one kind of equipment and get on with it. But there are still enough stations operating in the analog mode that we have to maintain and teach all that equipment. At the same time, there are all the stations that have gone digital, and we have to teach that as well. So, people come out of here having had both.

We start them in production doing traditional analog tape recording production work. We go into blade editing and splicing and all that stuff. I’ve found that this experience is really helpful when they move to the digital side of the house because the cut and paste functions are pretty intuitive when you’ve actually cut tape. They do everything from thirty-second spots, basic bread and butter copy and music spots, on up to elaborate promos and multi-track work by the time they are done. Part of how we fund running this station is sponsored public service announcements and underwriting announcements, so there is a steady stream of those that have real world deadlines that are very, very basic copy and music spots. At the same time, we’re doing promotions and station promos and format pieces that can get fairly complex. Right now we’re about to launch an on-air contest with probably the biggest prize we’ve ever given away to a listener, which will be a trip to Florida, and that’s a fairly elaborate multi-track production effort with a whole bunch of spots and a lot of sponsors involved.

JV: When you get sponsors involved in something like this, do you end up having to produce actual commercials for them?

John: No. We are a non-commercial station so we are very, very careful about the FCC rules regarding commercial content. We do promotional participation spots. There are a lot of companies looking to promote something who are willing to provide merchandise prizes in exchange for promotional mentions that can be done within the non-commercial rules. At the same time, we are a state agency. We are licensed as a state college, and there are some state laws we have to be careful of. We don’t actually ever give anything away here because if the prizes belong to the college, it would be against state law to give them away because they would be public property. So, other people give things away and we help them do that.

There is one area where we do get into advertising, and that is for non-profits, and that falls again within the non-commercial rules. So, we do a lot of straight ahead advertising type spots, which would be a commercial spot for our own college, other colleges in the area, other educational organizations, and for charitable groups. We’ve been very active, the station has, in working with fund-raisers for organizations like the March of Dimes, the Elks Club, and other non-profits in the market.

JV: So there is some hands-on commercial production, but you’re not cutting spots for the local bar down the street.

John: No. But we may do a station promotion where we go out and get local businesses to sponsor a promotion in order to provide prizes. For that, we’ll do promos and sometimes underwriting spots as well. Those can get very creative. Since the eighties, non-commercial underwriting has been a little less restrained than it used to be. You’re limited by being prohibited from having a call to action, a qualitative or comparative statement, or a price quote; but you can be descriptive of businesses’ products and services. I would say we’ve done some underwriting spots which are entirely within the non-commercial bounds but which are as creatively done and as effective as a lot of commercials that I’ve heard.

One of the other things we produce is a weekly public affairs show, a short form one. It’s a sixty-second feature we produce for Pierce County Crimestoppers. Crimestoppers exists all over the country as an effort of local business and law enforcement to reduce the crime rate, and we produce the Crimestoppers sort of “Crime of the Week” program feature. That’s distributed and aired on six radio stations in the Seattle market.

JV: What do you teach about copywriting?

John: We start copyrighting with journalism of all things, again because the discipline of the language is most easily introduced writing news stories. And from there, we go to writing spot copy because the grammar of broadcast or spoken English is already in place at that point. It’s just a matter of shifting gears to being a little bit more excited about things than you’d be in a news story.

One of the basics we try to get across is to get to the point. Whether we’re doing spots or whatever, even if it’s news stories, I find the hardest thing I have to do with students is overcome what their English teachers have taught them to do. I don’t want to erase that knowledge, and I don’t want them to think it’s not valuable, but they want to write prose when they first get here. They want to write stories, and they want to write plays. And to get them to shift gears to do spot copy that just punches home the key points is really tough because they want to write an essay.

JV: Well, at least their doing one of the things we hear a lot about, and that’s to make a story out of your commercial.

John: Yes, it needs to be a story, but it needs to fit in thirty seconds. We don’t have an hour. I think that’s really the biggest and first stumbling block with the student beginners is that they write too much prose that goes on too long. I use the RAP Cassette tapes a lot because the tape is worth a thousand words. When you can listen to a spot that paints a picture in thirty seconds with some sound effects and some phrases, it’s really easy to get from that to writing copy rather than trying to get from writing a term paper to writing copy. Being able to play those examples in class has been very effective. I use them all the time. When you do the annual awards, we sit down and vote on them in class. The RAP Cassette is the production version of what the air-check people do. I use the video air checks from California Airchecks and some other companies, and we do a lot of monitoring of the stations in the market. So, when we’re in the classroom, there’s a lot of discussion and sort of analysis of what other people have done. And we’ll go through spots from the Radio And Production tape and kind of pull them apart. We’ll ask, what’s the image, what’s the picture in your head, why does that work? It’s actually one of the most useful tools I have in doing that part of the class.

JV: One thing about today’s radio that must be an advantage to your students is the fact that you don’t have to have that big, deep voice to get into radio anymore, or into voice-over for that matter.

John: It is nice that radio has evolved to where normal people are okay on the air. I rarely have the traditional, old-fashioned, giant-pipe radio voice in this class. However, I actually have one in the class right now. I have a guy who sounds like Gary Owens all the time. It’s almost frightening because I get a voice like that maybe once every three or four years.

I always have a wide range of voices, and it’s somewhat neat from my perspective because this is a lot higher turnover than you’d have in a professional setting. If you tried to run a professional station with the staff turnover that we work with, you’d be out of business. I mean, we can’t fire anybody, but they leave anyway. So there’s a never-ending parade of different voices through here, both male and female, and the variety is just endless. Some people take to it quicker than others. Some people read better than others. But there’s room for many different voices, and I’ve been happy about the way radio sounds when it’s not all giant, scary radio voices. I kind of like the idea there are lots more women on the air now, too, because I think that lends a real variety to what we’re listening to as well.

JV: Does your course get into anything that can prepare a student for a career in voice-over work?

John: Well, it is an entry-level program. This is not the only thing you need to do if you’re going to have a career in radio and production and voice-over work. You’re probably going to need to do some more things and learn some more things beyond what we do here. This is really a launch pad that can send you off in a variety of different directions. We talk about working with different kinds of microphones and getting them placed right and getting the most out of a microphone for whatever your particular natural sound happens to be. We talk about pacing and breathing and phrasing and how to mark up copy. It’s pretty basic stuff.

I try to get people to find out just how broad a range they have. Some people don’t need to do this because it comes to them naturally, but somebody who is struggling to find a range, I’ll ask them to force themselves to record a piece of copy at extremes of different emotions or extremes of pace or level. Then I’ll go back through the playback with them to see how they hear that difference.

When I first did college radio, I was on the big carrier current AM station that went to about four buildings. I sat down there, put those headphones on, and started to speak words into a microphone. And I thought I sounded pretty cool. Then I played back the tape, and I sounded like a dead person. It took a long time to calibrate the inside of my head to hear me the way other people heard me. Again, going back to the beginning, the first on-air work that they do here is news because it’s really structured. I have them record every single newscast, and they have to sit there and listen to themselves with the copy in their hand before they leave that room. That way they get a feel for the difference between how they thought it sounded and what it really sounded like.

JV: You mentioned having both analog and digital equipment in the studios. What are you using?

John: An incredible collection of stuff, both in terms of its capability and its age. On the analog side, we have quite a collection of tape decks. I’m thinking of charging admission for people who like tape decks because we have them all. We have one Ampex 350 transport still in use in the lab—I’m probably going to retire that this year, but it breaks my heart to do it. Most of our on-air production work that’s done on tape is done on Sony MCIs, which are very capable but a little temperamental because they have a few years on them, and the logic circuits are beginning to go nuts. We do a lot of plugging circuit boards in and out of those. We have Ampex and Crown and MCI tape decks, and I have a couple of ITCs that are actually in storage that we just retired. These are the 2-track decks. And we have half-inch 4-track capability on the analog side as well.

On the digital side, we’ have 360 Systems’ Short/cuts in the air studios for doing phone editing. We have a 4-track workstation built around an Akai DR4, which is no longer in production. They make an 8 and a 16 now, I think. We actually built a digital workstation in the big steel roll-around console that used to have an MCI tape deck in it. That’s made out of a DR4, a Yamaha SPX1000, a Soundcraft Spirit eight-channel mixer, and a couple of powered speakers that are on board. It rolls around on those big casters, and we can take it in the classroom, take it in the office, put it in the studio, and patch it into any control room with patch cords. It’s a pretty utilitarian device. Then our 16-track is a SAWplus workstation that’s PC based. As the students work their way through the various pieces of equipment, that’s where they’re going. They start out in a production studio with analog, then multi-track, and then 4-track digital and the hard disk recorder. Then we go to the SAWplus computer-based workstation.

JV: How do the students take to the SAWplus once they finally get to it?

John: They love it. But there’s a funny learning curve. There’s this big entry barrier initially— unless I have somebody who has been playing with computer audio at home before they ever get here. But usually, they’ll sit down in front of it, tear their hair out, look at it and get very frustrated for about an hour. Then after that, it just takes right off.

The IQS people have put together some very good SAW tutorials that are easy to work through. And if you’ve cut tape before, and you’ve already been through the hard disk workstation getting all those tracks up on the screen, once you get used to where to click the mouse, it just opens up like watching a flower bloom.

JV: What’s one of the hardest things to teach about production in the course?

John: Overcoming inertia, I think. People are sometimes afraid of the equipment, and they’re afraid to try something because it won’t work. Then once you get them to realize that it’s not going to explode when they touch it, then they start to take off. I think the other thing I run into is so basic and yet, it’s been a real stumbling block, and that is maintaining consistent audio levels. I mean, that is so basic that when you’ve done it for a while, you don’t even thing about it anymore, but beginners don’t think about that at all. And the worst—and I hope I don’t insult anybody here—but the worst are the people who have done mobile DJ work and club DJ work. I’ve never done that, but, apparently, when you do that, levels are not an issue at all. So the guys who are really good mix DJ people are sometimes the ones who come into this setting and have the toughest time maintaining the technical standards on the thing, and they just don’t understand why all that distortion is in there. And they want to know where the magic box is that removes it, and they’re very disappointed to find out that we don’t have one.

JV: What do most of the students in the course expect from radio? What are they out to get? Do they all want to be superstar DJs?

John: Well, I don’t know that the word superstar comes up, but in all honesty, even at this point in time, the magnet is probably the prospect of being an on-air performer in some way. Very few people come in the door predisposed to be traffic managers, Account Executives, Production Directors or anything else, because what they’ve grown up with, the younger ones in particular who are coming right out of high school, is that DJ mystique. Even though the technology and how radio is done behind the scenes has changed so dramatically in the last few years, it doesn’t sound any different. So they still imagine that there’s some person in there with a bunch of tunes, and it’s a real eye opener when they walk in and discover that it’s a room full of computer screens and a bunch of printers that are going all the time spewing out logs and schedules and people going from room to room with computer disks in their hands. That’s not necessarily the picture they had in their minds when they first came through the door.

I think what we do in the program is try to open people up to a lot of the possibilities in the business. We just put an Enco hard disk system on the air, and most of the time it runs in a live assist mode. But that has brought about a real shift in the students’ thinking because it really brought home the idea that the mechanics of shuffling disks and carts in the on-air studio are not really all that important as opposed to creating the content that goes on those disks. So having that system in place has quickly shifted the student interest much more heavily into the production side of the building from the on-air studios.

JV: What kinds of successes have you seen from the students over the years? Have you had some people get out and really do well for themselves?

John: Yes. I don’t know if we have any superstars, to use your term—I don’t know what that even means today unless you’re talking about Howard Stern or a Rush Lindbaugh. But there are people from the program all over the country. Sometimes I don’t hear from them for a long time, then they pop up. I got an e-mail a little while back from a guy who graduated from the program in the late eighties, and he’s working for the Clear Channel stations in Orlando, Florida. I had no contact with him for almost a decade. Suddenly, I got an e-mail, and it was a nice feeling to get an e-mail from somebody who says, “You know, if it hadn’t been for that program at Clover Park, I wouldn’t be doing this now.” When you get that kind of feedback from people, that’s as good or maybe better than a good rating book.

We’ve had people come out of here—and when I say “we,” there are some other part-time people who help me with this; I’m not alone. We’ve got a guy right now who went right from here to the Ackerly stations in Seattle, KUBE and KJR. We’ve had people go all through the Northwest, down into California, and as far as the East Coast. The fellow who e-mailed me from Florida actually went to his first job on Long Island in New York from here, and that’s really a kick to see that happen.

With the changes that have gone in recently at the facilities here, the changes we have planned for the future, and the curriculum that we have now, I’m starting to feel better about the fact that we’ve got people coming out of the program who do want to go into production work or directly into marketing and promotion, and some of them are starting to do that. So, yes, most of them come in the door thinking on-air personality, disk jockey, performer, but when they get exposed to what is really a full-scale working radio station environment and to all the other things that go on, a lot of them shift that direction while they’re here.

I’m really proud of what the students do here and what they accomplish. If an individual is looking to get into radio, maybe they can’t come here, but I’m sure there must be some other programs here and there around the country that are like this. If you can find a facility that is really trying to do real-world radio rather than a campus radio or the sort of stereotypical college radio kind of thing, then I would encourage people to go do that.